Race, Place, History, and Progress in SC's Baha'i Community

- Louis Venters

- Sep 3, 2023

- 6 min read

This is a bit late in coming as a blog post, but the sentiments are as fresh as they were last May. That's when I first heard that my friend and esteemed colleague, retired professor of urban planning June Manning Thomas, had been elected, along with eight returning members, to the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of the United States.

First, a word about what that means. There is no clergy in the Baha’i Faith; instead, the community’s affairs are entrusted to consultative bodies elected by all adults 18 years of age and up. In the case of the National Spiritual Assembly, delegates elected at the local level across the country assemble once a year to elect the national body from among all the Baha'is in the 48 contiguous states. (Alaska, Hawaii, and the territories have their own national bodies.) Free of nominations, campaigning, moneyed interests of any kind, or even references to individuals, Baha'i elections from the local level to the global are carried out in a peaceful atmosphere of reverence and joy. I've had a chance to participate in this process since becoming a Baha'i more than 30 years ago, and a large part of my research and writing as a historian has involved study of the rise and development of the Baha'i administrative system in South Carolina and around the world. To the best of my knowledge, this is the most dignified, most effective expression of democratic self-government that humanity has yet brought into being.

This year, there was an unusual case of a tie for the ninth place on the National Spiritual Assembly. According to a Baha'i policy of affirmative action that's been in place for about a century, had one of the two tied individuals been white, the seat would have automatically gone to the minority. But since both of the individuals were minorities, a tie-breaking vote was held. This included contacting by phone delegates who had already left the convention to catch early flights home to the West Coast. As I understand it, the tellers (who were also fellow-delegates) gave everyone a ballot with only the two names of the tied individuals, and June received the higher number of votes. Then the full results of the election were reported to the American Baha'i community. Only the delegates know who the other individual was, and none of the rest of us are worried about it either way.

Have you ever heard of an electoral process carried out with such a combination of transparency, dignity, and trust?

In fact, in the Baha'i system discussion of individuals before or after an election, even in a positive light, is strongly discouraged, because even a hint of partisanship or bias strikes at the conceptual heart of the Baha'i Faith: the absolute equality and dignity of all human beings and the fundamental unity of the body politic.

If that's the case, then why this post that seems to single out an individual?

Aside from giving me a chance to marvel at the global system of spiritual democracy that the Baha'is have built, it's mostly a reminder of the long history of dynamic interactions between the Baha'i Faith and the Black freedom struggle in this country, and of the pivotal place of South Carolina in the growth, development, and identity of the American Baha'i movement. June's life and work seem to embody a number of these important connections, so I'm willing to take the risk of offending her modesty by offering a few reflections.

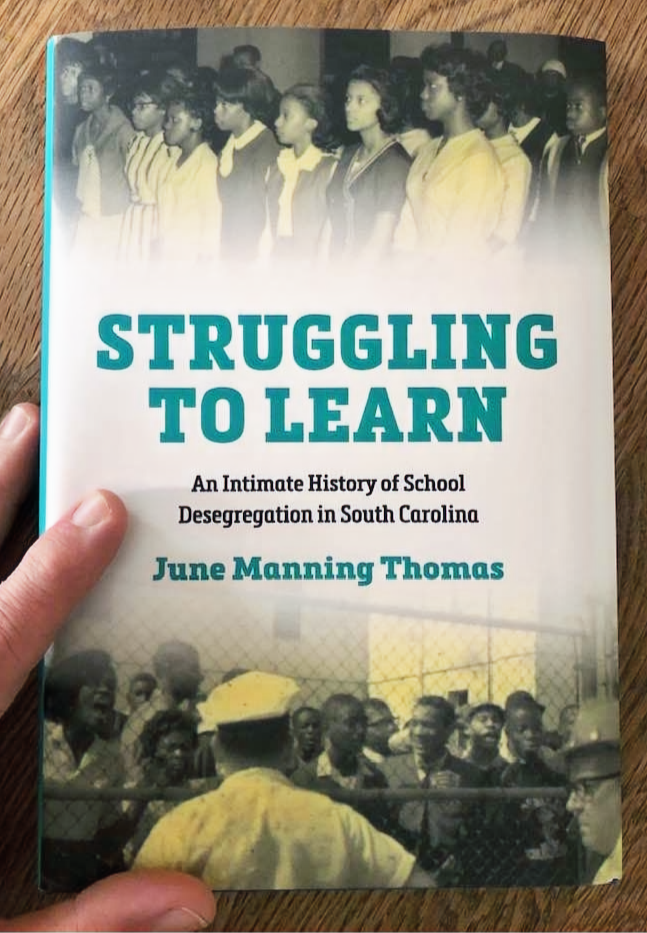

June was born into a prominent family of educators, ministers, and activists in Orangeburg, South Carolina, where she was one of the first handful of Black children to desegregate the local schools in the 1960s. In her new book, Struggling to Learn: An Intimate History of School Desegregation in South Carolina (University of South Carolina Press, 2022), she weaves together her own family story with that of the Black Orangeburg community and of the broader movement for (and against) the dismantling of Jim Crow in South Carolina. Despite the state's outsized role in the movement, as, for example, Dr. Millicent Brown has documented in her great online exhibit, "Somebody Had To Do It: First Children in School Desegregation," precious little scholarship has been published about school desegregation in South Carolina. So this account focused on Orangeburg—which was such a hotbed of activism for so long, due in no small part to the presence of two Black universities—is especially welcome. Over the past year, June has done a number of talks about the book, virtually and in person, including more than one trip to South Carolina. Last summer I had the chance to attend her talk at the Cecil Williams South Carolina Civil Rights Museum in Orangeburg; she's also been to Clemson University and the University of South Carolina in Columbia.

I'm so grateful to June for doing the challenging research and writing to bring the stories of her family, community, and state to the page, and to USC Press for producing such a handsome volume and really supporting the marketing of the book. Thanks to Ehren Foley, my former grad school classmate who is now acquisitions editor for the press, for doing so much to make this happen. And by way of another professional connection, I'm delighted that Cecil Williams, the distinguished photographer of South Carolina's civil rights movement whom I met when he hosted June at his museum last summer, is bringing his wealth of experience to the work of Preservation South Carolina, the statewide organization leading the way in protecting our irreplaceable historic built environment, as a board member.

June first encountered the Baha’i Faith in Orangeburg and then as a student at Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina, which I touch on in my book, A History of the Baha’i Faith in South Carolina (History Press, 2019). The first Black student at Furman, Joseph Vaughn, an activist who was part of the growing Baha'i youth movement in Greenville, had enrolled the year before. So June was part of a second small cohort of Black students, which included Lillian Brock Flemming. Mr. Vaughn and Ms. Flemming went on to long careers as educators in the Greenville County schools; Ms. Flemming has served on Greenville city council since 1981. In the early 1990s, soon after I'd become a Baha'i, Ms. Flemming was my beloved geometry teacher at Southside High School--although it would be many years before I understood how we were linked historically.

June left South Carolina for Michigan to complete her undergraduate and then graduate studies, eventually becoming a professor of urban planning at the University of Michigan. During her long and distinguished career, her scholarship focused on the ways that race and class discrimination have affected the shape of our cities, and how we might learn to rebuild urban spaces to be more just, equitable, and prosperous. You can get a sense of her impressive body of work at her faculty page at the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning and on her own great website.

Over the years, June served the Baha'i community in a number of capacities locally, regionally, and nationally, always bringing her professional experience in planning, place, history, and equity to the table. Several times we overlapped as delegates to the Baha'i national convention. One year, she spoke with passion and clarity about the challenges that generations of federal and state housing and transportation policy represent for the Baha'is' interracial, cross-class community building efforts. As a historic preservationist who was also working on the legacies of segregation in the built environment, I was so glad to hear another Baha'i bring such a depth of historical analysis to consideration of the community's contemporary efforts. I sought her out after the session and practically begged her to turn her comments into an article so that others could benefit. And she did! It eventually appeared as a chapter in the edited volume, The Baha'i Faith and African American History (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), to which I also contributed a chapter on South Carolina.

To my knowledge, June is the third person born and raised in South Carolina, all African Americans, to serve on the National Spiritual Assembly. Louis G. Gregory (1874-1951), a Washington resident originally from Charleston, served for a total of sixteen years from 1912 though the 1940s. An attorney, he helped draft the National Spiritual Assembly's constitution and bylaws, among many other foundational services. Alberta Deas (1934-2016), another Charlestonian, was instrumental in the growth campaigns of the 1970s and 1980s that resulted in unprecedented numbers of Black southerners becoming Baha'is. She served on the National Spiritual Assembly during the 1980s and 1990s and was the founding director of Radio Baha'i in South Carolina. Two other long-time residents, Jack McCants (1930-2023) of Greenwood and Tod Ewing (b. 1953) of Columbia, served in the 1980s and 1990s. It seems like an impressive record for a such a small place!

But for anyone familiar with the history of the Baha'i Faith in South Carolina, it comes as no surprise that the state that witnessed the largest response of people to date in North America to the Baha'i message, mostly by African Americans, has tended to punch above its weight in shaping the priorities and policies of the larger American Baha'i movement for so long. With the recent launching of a new global plan to hone the Baha'i community's society-building efforts and the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Louis G. Gregory Institute last October, there's every reason to think that the Baha'is of South Carolina will continue to make major contributions to the progress of their state and country in the turbulent years ahead.

Komentáře